|

KITCHEN COMMERCE and SUMMER

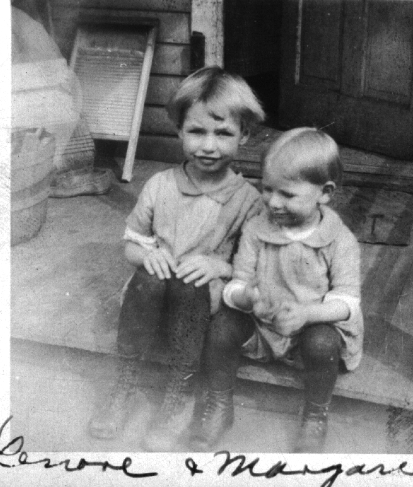

MEMORIES Our end of Foundry Street was bounded on the West by Farmer John's field which I remember as mostly fallow, and on the East, by the railroad and the Glen Alden iron foundry. This is the microcosm that inhabits my memory. In the field, my friends (mostly boys) and I built ‘bunks” , lean-tos or shacks we called our clubhouses, in which we tried often to work out some initiation rites, but never did. If I was successful in purloining some William Penn tobacco from my father’s supply, we wrapped it in pieces of newspaper and attempted to smoke it. Or we made sling guns, using bands cut from inner tubes which we wrapped around blocks of wood to mimic a revolver. When the piece of wood holding the rubber was released, the rubber flew toward a target. My best friend Louis Mascagni and I had mounted one of these on an upended peck basket, where it became a machine gun. Poor Louis -- he was teased unmercifully when he claimed priority of invention for us and limited access to it: : “Only Lenore can use my guns" in our games of cowboys and Indians. We played Reliev-o and hide-and-seek. Or my sister and I, in rare collaboration, would sing the songs of the day (where did we hear them?): “Carolina moon, keep shining..." These are summer memories. And to the summer belongs the procession of itinerant peddlers and traders who came to the immigrant families. On a balmy afternoon, when the housewives would have done their housework, and, as my mother did, changed their aprons and sat in the rocker on the porch, the seller of fortunes came with a parrot perched on his shoulder and a pegboard in his hand. For a nickel, which he nipped from your fingers, the parrot pecked out a piece of accordion pleated paper from one of the holes in the pegboard. Good fortune or bad fortune? It didn’t matter. “Thank you, lady,” screeched the parrot. Mr. Sutton, the huckster, came weekly in summer, his plodding horse pulling a wagon loaded with crates of vegetables and fruit. The horse waited patiently while Mr. Sutton, a somewhat taciturn man, dealt with his customers, mostly the Irish and Welsh families. The Italians had their own gardens, as did we... Still, though my mother did not patronize Mr. Sutton, I did taste Mr. Sutton’s strawberries. Mrs. Mooney sat on her front stoop and hulled them, passing one or two along to me, as I sat by her side. Farmer John's only commerce was with the man who delivered truckloads of grapes in the Fall, and we knew what he was going to do with those. |

|

|

Mr. Catrone, a presence — in bulk and in personality — lived at the end of our block. He bought watermelons from a peddler — with great deliberation. He would stroll up to the loaded wagon, select a watermelon, heft it, thump it, put it down. Then he would take out his pearl handled clasp knife and unfold the blade. Masterfully, he would cut a plug out of the melon, and if the rosy, juicy meat was to his liking he would pay. In the same manner, he bought his cheeses from another vendor. Only if the plug of cheese had reached his standard of aging would he pay. This was my first experience of connoisseurship. For me, his taste was surpassed only by another Italian who stopped at the corner of our garden where my mother had roses and mint and rue and dahlias, our amenity corner. He leaned over the fence, plucked a leaf of mint, bruised it, rolled it into a slender tube and tucked into a nostril — it was as though he had picked a rose and stuck it in his buttonhole — and he continued his walk. The most exotic and intimidating commercial visitor was a Turkish woman who dominated the space she occupied. She swaggered up the walk, greeted my mother with a flashing gold-toothed smile (more of a grin), and announced she had just what Ma needed. She came into the kitchen, sank in heap to the linoleum floor, her skirts billowing around her. She had slung her pack from her shoulder and proceeded to untie the knots that held the four corners of her pack together. As she did so, she extolled the quality and beauty and, especially, the priceworthiness of the things she was going to show my mother. She extracted length after length of printed cotton yard goods, toweling, dress lengths, all the while chattering away, "Cheap! Cheap!” And then suddenly, to me, “Good girl, get me a glass of water... good girl!” I gave her the water, and she went on. Ma did succumb to her sales talk. The lengths of material she bought joined many other such purchases in the upstairs bedroom, where we discovered them, many years later. |

|